Would I lease this

Qualities compelling, consumer HaaS products will share

I’d been thinking about HaaS for over two years before starting fragile. It started soon after my time at JUMP Bikes. Thinking back on lessons learned, I pitched a friend that transportation would become more about services and less about ownership. In a future rich with access to robo-taxis, micromoblity services and public transport, there would be little reason to have your own car. But I took it one step further—why should this be limited to cars? What other industries could this trend effect?

My friend agreed emphatically—so much so that I started to consider what would be a good hardware product for this business model. As I reasoned through possibilities, I developed a framework for thinking about what makes a hardware product compelling and practical as a service.

I’ve broken the model down into three parts:

- Qualities that make a hardware product more compelling for leasing

- Qualities that make it less compelling

- Extrapolating the trend to its limit

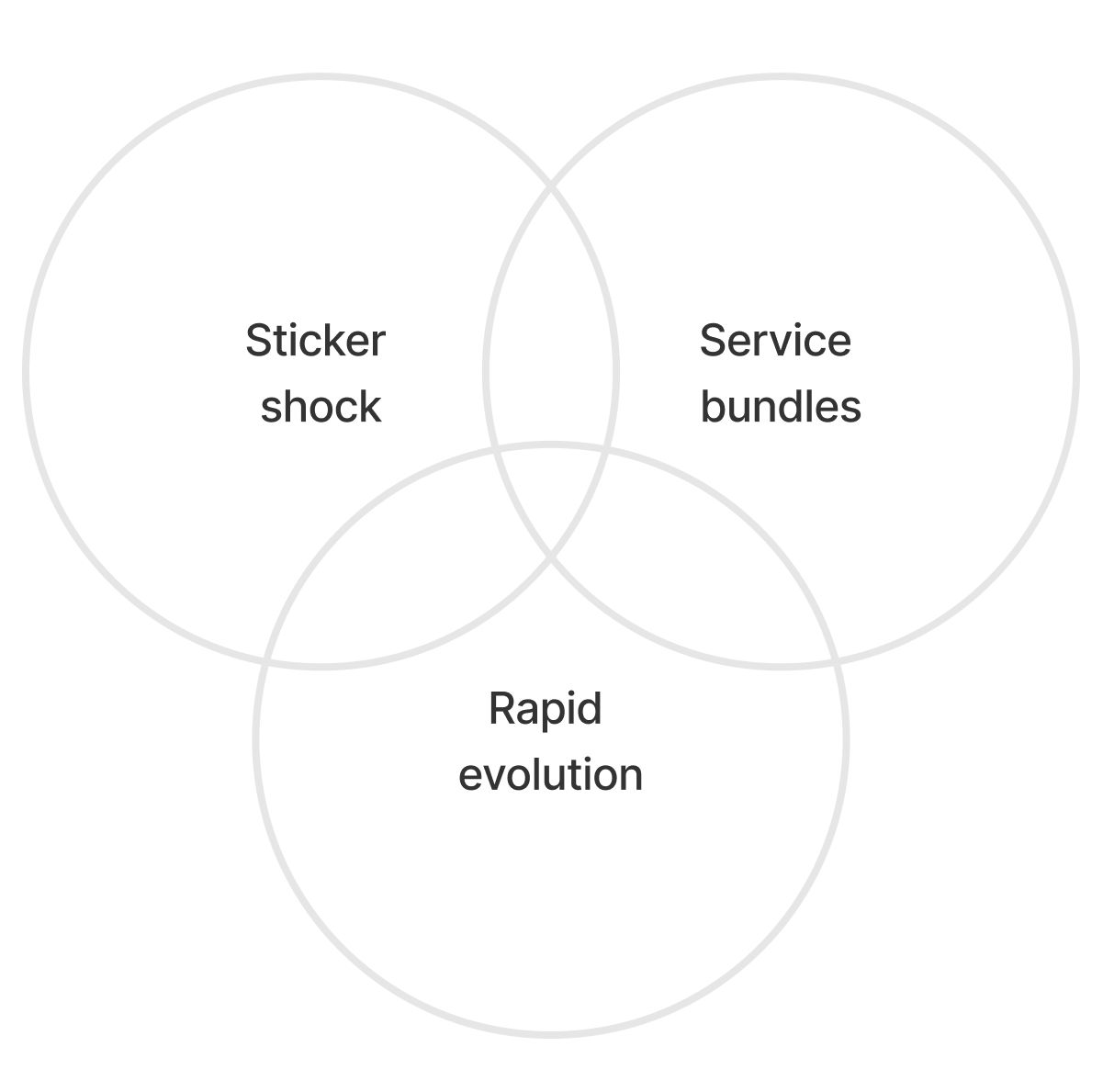

Part One — The compelling trifecta

There are three key factors that make a hardware product a good fit for subscription:

- Sticker shock - Friction the consumer feels from the upfront cost of a product

- Service bundles - Hardware made much better by additional services offered in tandem

- Rapid evolution - Rapidly changing technology and taste

Sticker shock

The obvious advantage a hardware subscription has over purchasing is the upfront cost. Take Sarah, an urban dweller considering whether or not she should get on the new ebike fad. She really likes the idea of commuting to work by bike but is concerned about how much she’ll actually use it. And where will she lock it? These concerns about lifestyle fit make a $3,000 commitment daunting. Now, consider an offering like Dance’s ebike. At $80 per month with no commitments, Sarah’s concerns seem less risky, and moving forward becomes a no brainer.

Service bundles

Sometimes it’s possible to reimagine ordinary hardware products by enhancing the offering with useful services. A great example of this is Peloton. An exercise bike is nothing new; but spice it up with some sleek industrial design, a big screen and a high-quality instructor and now you have a spin class in the convenience of your home. For the first few years of Peloton’s existence, they required the bike to be purchased upfront with a monthly subscription for the online classes. This year they saw the light and combined the two into a single monthly subscription.

The end user can more easily equate this monthly cost to a gym membership. Consumers are already conditioned to paying monthly subscription on a whole range of services; reimagining a hardware product in the same way makes it competitive and digestible.

Rapid evolution

I like good pens. The ballpoint pen has been around for almost 150 years, and in that time the technology has not changed that much. Owning a good pen makes sense to me because I expect it will still be useful to me in 10 years.

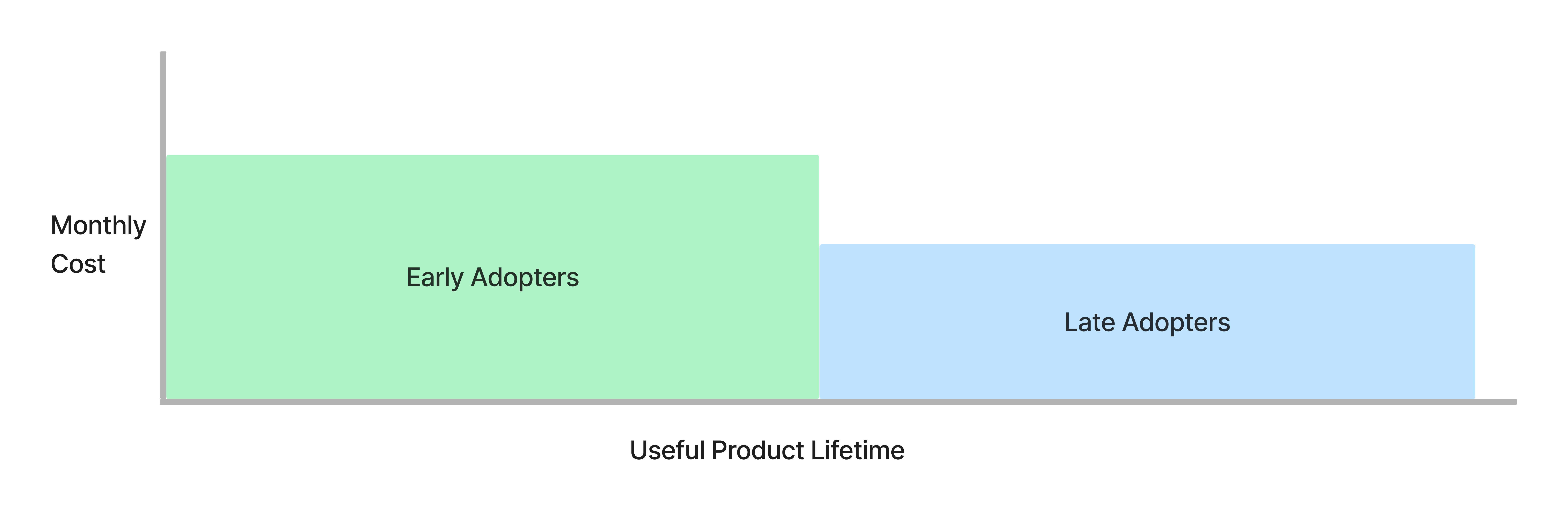

That is not true for many new technologies. A phone or VR headset can come out with some exciting new features from one year to the next. For some, there is a feeling of FOMO that drives us to buy the latest and greatest long before the last model has been fully utilized. But for every early-adopter, there’s also a person like my friend who still uses his 9 year-old iPad to watch Youtube videos in bed.

Rapidly evolving technologies, however, gives entrepreneurs the chance to create services that capture both these market segments—where customers willing to pay more for the latest and the greatest can continually upgrade their products, and customers who just want an affordable, functional product have access to a steady stream of refurbished hardware. A subscription service that eliminates the messy transactions between these two pools of customers is a much more attractive option than the current second-hand market.

The Venn Diagram

Any hardware product that checks 2 of more of these boxes would be a compelling candidate. All three you should probably have started this business already.

Part Two — Practical constraints

In the equation of compelling Haas products, there are definitely factors that make the business less practical. Some may be overcome by ingenuity or future technologies; others may never be practical for a hardware subscription business to manage.

Logistics

It’s important to remember that most HaaS products will have more than one subscriber in its lifetime. This means several two-way trips between the business and customer. Moving things requires both time and energy—and moving big things requires a lot of energy. Shipping a phone is insignificant compared to production cost. But shipping a couch might be more substantial. There is also the complexity of packing, unpacking and installation that must be accounted for. The most logistics-intensive products may require investing in local operations that might only pay off in bigger cities. If the logistics component is too large, the unit economics of the business may never add up.

Servicing

In my experience, servicing is one of the most underestimated costs—particularly at high volumes. Fixing things is hard—sometimes even harder than manufacturing the product in the first place. A leasing business will need to service its products multiple times to get the most value out of them. For high value assets like airplanes or ships, this is already happening all the time. But for lower value items like consumer electronics, the trend has been towards replacement rather than service.

Lime scooters learned this the hard way with their first generation product. The retail-focused hardware was not robust. It would break after just a few days in the field and often couldn’t be serviced economically. This accelerated depreciation put their entire business in jeopardy until newer, in-house hardware improved their vehicles’ service life.

Part Three — HaaS to the limit

Once upon a time, computers were limited to institutions; now we have supercomputers in our pocket. Like technology, business models evolve over time as behavior changes and new efficiencies are discovered. It’s useful to take a step back and consider what constraints exist with the Haas model when stretched to its theoretical limit.

Appreciation vs depreciation

One of the great advantages financially savvy individuals have is an appreciation for appreciation. A HaaS entrepreneur must likewise develop a good understanding for how appreciation and depreciation applies. To understand these concepts better, let’s look at a Toyota Corolla and the Rolex Submariner 16610 watch. They both start their journey in 2011 when they’re purchased new, with cash.

Toyota Corolla

The Corolla is purchased for $17,600. Five minutes after driving it off the lot, its resale value drops to about $16,000. After the first year, it’s fallen another 15%. With time and use, the car becomes less valuable. This is an example of depreciation. Sure—the car fills a need and provides a lot of utility—but there’s an inverse relationship between utilization and resale value. Eleven years and 130,000 thousands miles later, the car is worth about $7,000. It’s deprecated 60%.

Rolex Submariner

The Rolex is purchased for $6,500. It’s worn everyday because you would too if you spent $6,500 on a watch. Luckily, the stainless steel body is durable, and the movement lives up to Rolex’s high standards. After 346,896,000 seconds the watch is valued at $10,775. The timepiece actually benefits from a rich secondary market for luxury goods and appreciated 63%.

Consumer should trend towards leasing depreciating assets

While it’s debatable whether the Rolex was a sound investment (it only maintained ~4% ARR), it clearly held value better than the car. In terms of growing one’s net worth, depreciating assets are not a good investment because by definition, their value goes down over time. By owning that asset, you are owning the right to lose money on it. Instead, leasing makes the business responsible for that depreciation. In general businesses will manage this more efficiently than the consumer.

We now have the building blocks we need to make a statement about Haas to the limit. If we leave logistics and servicing aside, the tenet looks like this:

Haas tenet

The Haas model should ultimately be applied to any non-commoditized, depreciating asset.

Currently the vast majority of consumer products are still purchased rather than leased. With enough time HaaS could become a dominate business model. However, for those exploring the space, I hope this framework gives you some tools to assess which products are a better fit for disruption, now.