Grappling With Gantts

Uncertainty and the Fog of War

In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.

~ Dwight D. Eisenhower

We’ve all experienced the demoralizing feeling of hiking to the top of a ridge, only to discover that you’re much further from the peak than expected; but you should forgive yourself for the mistake. It’s the outcome of being a two-meter tall spec, traversing many-a-mile across a three-dimensional surface. You are limited by your eyes, whose vantage can only see a small fraction of the path ahead—and after an exhausting ascent, it’s easy to succumb to wishful thinking as well. But it’s a challenge that project managers grapple with everyday.

One of the favorite tools used by managers to navigate a project journey is the Gantt. It’s been around for over a century. It’s basically a bar chart where each row represents some activity along with the amount of time it’s expected to take and how it relates to other activities’ timelines. Therefore, making a Gantt requires breaking down a project into pieces and considering their dependencies. This is a very useful exercise. But over reliance on Gantts is one the most common traps project managers can fall into. Let’s see why.

“Eggantt” Parmesan

As a short exercise, let’s consider a project called “Cooking Eggplant Parmesan.” We start with an unordered list of tasks:

- Peel and slice eggplants

- Preheat oven

- Slice and grate cheese

- Prepare breading station

- Simmer marinara sauce

- Bake eggplant parmesan

- Bread and fry eggplant

Next we need to assign time to those tasks and put them in the correct order.

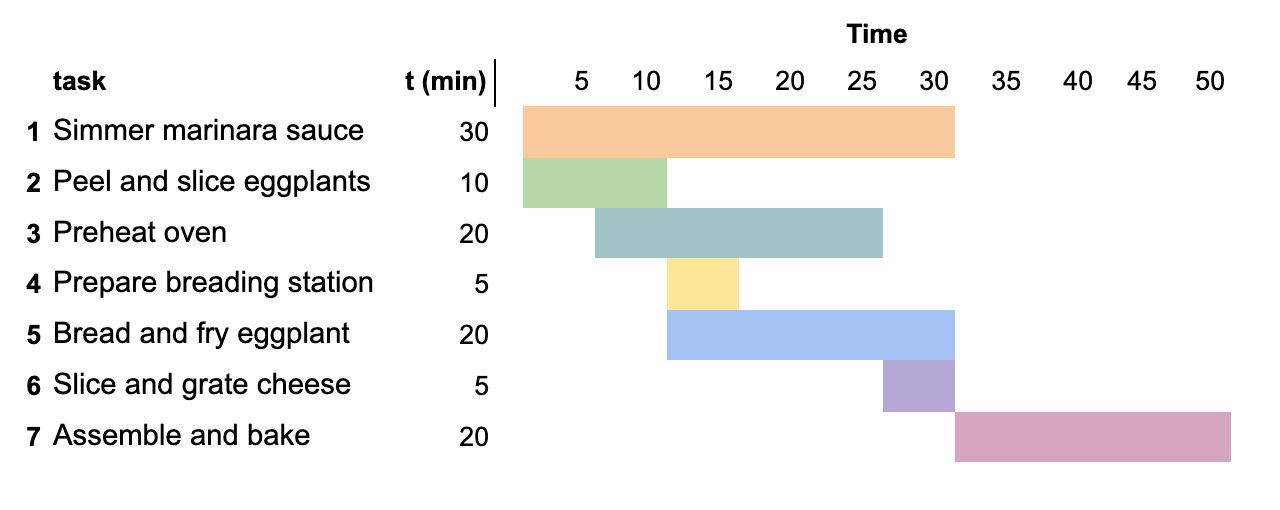

We are going to simmer the sauce from the beginning to intensify its flavor. While that is happening I’m going to slice the eggplant. Because I’m an excellent cook, I’m going to salt that raw eggplant and let the salt work its magic while I set up the breading station, etc. etc. The end result might look something like this:

My food is tastier because of the thoughtful steps I planned—and I managed to complete it in half the time versus placing each task back-to-back. Anyone watching this carefully timed dance will be forced to say, “wow—that guy can cook!” In reality, chefs are constantly relying on mental Gantts without which they could never get through a dinner service.

In this first example, however, we are already exposed to the Achilles heel of Gantts—their dependence on having a deep understanding of all the required tasks. As we will see, most projects don’t have the luxury of a developed routine. Reliance on Gantts, therefore, is often a recipe for disaster.

Raising the Stakes: Brunch

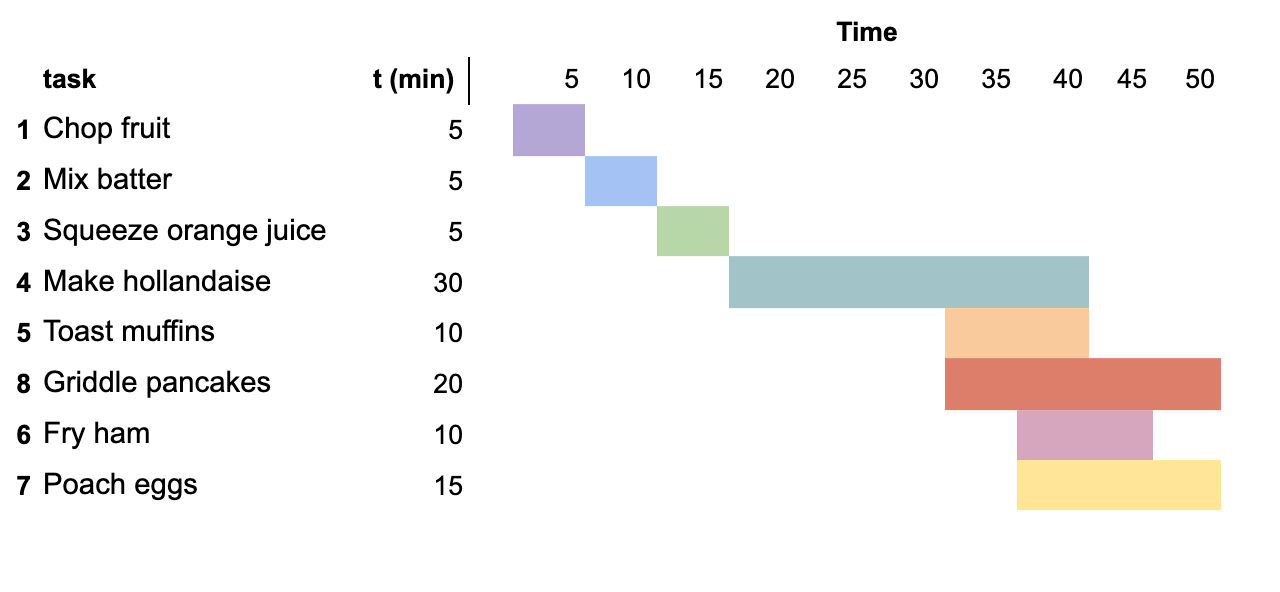

Instead of cooking Italian for five, let’s consider cooking brunch for ten: eggs benedict and pancakes. My service plan might look something like this

Armed with this strategy, I begin brunch. The first 15 minutes are confidence-inspiring. Everything goes according to plan—until we get to the hollandaise. The delicate sauce turns into scrambled eggs 10 minutes into simmering. I need to restart. This unplanned event has thrown me off my game, and now the muffins are starting to smoke. I can scrape the burnt bits off to get by—but I’m in a rush now, so I don’t give the eggs long enough time to poach. The first eggs benedict comes out raw and goopy. I get really stressed out, stop checking on my hollandaise, and it splits again. My pancakes—usually a consistent golden brown—are blackened and shameful.

The amused or irate diners will say, “wow—that guy can’t cook!”

What just happened? Disillusionment!

- I have a well laid-out plan

- I start to execute

- Small deviations occur

- I make increasingly erratic decisions to get back on track

- As things break down, I am forced to recognize the limitations of my initial plan

I’m not a professional chef. Cooking for so many people was a project outside my typical realm of experience, and therefore, my model was wrong. My dependencies and time estimates turned out to be off. But these were just first-movers in the unfolding disaster. Because of the strict order of operations, my small deviations had a compounding effect. A ruined sauce meant starting over. Starting over meant other dishes getting cold or being burnt. The ensuing stress further compromised decision making. Choreographing this unstable model is like trying to balance a pencil on the tip-–it will inevitably tip over.

Grappling with Uncertainty

Military historians love to tell us how important situational awareness is. Campaigns and wars are won and lost on the imbalances of military intelligence. It is the justification for scouts, spy satellites and espionage. If you ever played real-time strategy games (RTS) you were likely exposed to the concept of the Fog of War. It obscures the unexplored parts of the map and opponents’ activity.

For most of my childhood I had a dial up connection. (No, I’m not that old, I just grew up in rural NH). Because I did not have the bandwidth to play against humans I mostly played against the computer. Unsurprisingly, the computer was very predictable. I never needed to explore the map because, even if I could see it, I would know what the AI was doing. I was the professional chef on the battlefield, consistently winning and feeling very good about myself.

Playing against humans was a bit different. I was slaughtered. My formulaic gameplay made me predictable and my opponents’ better exploration of the map meant they were always one step ahead of me. I was constantly humiliated but what I learned is this: the players who successfully manages the fog of war inevitably win. Those who don’t are always reacting, never planning ahead for uncertainty of what’s beyond there current field of vision.

Gantts - Assuming there is no fog of war

I often think about time itself as playing the role of the fog of war. The things closest to us in time tend to be the most predictable. The further ahead we try to peer to more uncertainty in our model. This is why Gantts are often an exercise in arrogance. At most, they provide a false sense of security. At worst, they can lead to abject failure. This is because we are really truly horrible at predicting the future. The farther away from the current moment, the more obscured by fog things become.

Countering this tendency requires deep reflection of a single question.

How deeply I understand the problem at hand?

Are you like the chef, who has cooked their dishes hundreds of times? Or are you working on a new, hard problem, barely keeping your head above water? If you have the self-honesty to recognize that it’s often the latter, then there are better tools at your disposal. We’ll explore some of these next time. In the interim, create all the Gantts you want…but be prepared to update constantly as time reveals new parts of the game board.